I personally don't think the "good old days" were all that great.

There's been huge improvements in the way we write and use code and build our systems. And I would definitely not want to go back to the way it used to be done. Not for for love or money.

But the article does raise some good points about the inherent danger of losing basic skills in the process of acquiring more sophisticated tools to work with.

I don't know if it's the case with coders, but in my world of network technology, I'm already starting to see a problem. Many of the next-gen engineers I see coming out are great at dealing with all the latest and greatest tech. They can make the newest Cisco boxes sing like a diva. And they definitely know a lot more about them than I do.

But if you put them in a mixed environment with a lot of legacy equipment (i.e about 85% of the environments out there) they have problems. I suspect it's because the bulk of their training was on specific devices and products rather than core technologies. As a result, their knowledge is miles deep - but only a few yards wide. Show them something they've never worked with that's being balky, and their most common response is to suggest getting something "more up to date with the current state of the technology." Forget that a simple tweak to the setup - or replacing a suspect CAT-5 cable- would fix the problem in a jiffy.

The other problem I'm seeing more of is what's referred to as "menu thinking." The way it works is to look up the problem and apply the recommended fixes in sequence until the problem is resolved. And if the recommended fixes do not cure the problem, quit and wait for an updated fix

from the manufacturer.In short, if it ain't on the menu, there's nothing to be done.

Understanding the <*groan*> OSI model (or how TCP/IP and the various protocols actually work) isn't just a boring academic exercise. Well...I'll admit it can be pretty boring. But it's hardly academic. Because if your shiny new server or data switch starts acting up, knowing how that device works on a

fundamental and generic level allows you to troubleshot and fix it. Even in the absence of relevant guidance from the manufacturer.

That's the mark of a true professional:

the ability to remain effective in the absence of specific knowledge or expertise. Plus the ability to extrapolate from what knowledge and expertise you

do posses.

And it has real world benefits. I've gained a reputation with my clients over the years of being "the guy" who can fix anything. It's an exaggeration, although it's not too big a one. My record of "big wins" is pretty solid.

But it's not because I'm super-brilliant or incredibly well trained. My secret weapon (if I have one) is very

low-level and

basic understanding of how computers and networks actually do what they do. With that framework in place, everything else is a matter of filling in details as and where needed. And extrapolating from that to identify solutions for new situations. Because on a certain level, all technical problems are the same.

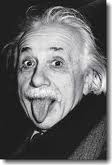

Albert Einstein had a cute way of looking at that: "You see, wire telegraph is a kind of a very, very long cat. You pull his tail in New York and his head is meowing in Los Angeles. Do you understand this? And radio operates exactly the same way: you send signals here, they receive them there. The only difference is that there is no cat."

That's the real difference between being "trained" and being "educated." Walking away from the basics with the argument it's no longer "relevant" may get you 'trained up' and 'tested out' quicker. But it also leaves critical holes in your understanding of the technology you work with.

The real trick is to be aware of those holes and fill them in as quickly as possible.

That, and not getting so put off by all those old guys sitting around the cracker barrel, jawin' about how tough

they had it, that you decide you'd rather not do it.